When I Say Portfolio…

When many people think of Portfolio, one of the first examples that comes to mind is a Financial Portfolio, a summary of someone’s financial assets (stocks, bonds, mutual funds, etc.). It makes sense as to why that is the case – this notion of a Financial Portfolio has been ingrained in us. You don’t have to look far to hear or see an ad from some financial management company pitching the latest buzz-words about how your portfolio needs to be “actively managed”. You might hear things like “we need to diversify your portfolio”, or “our firm offers automatic portfolio rebalancing” – they will argue that what is inside the portfolio is just as important as the process of making sure that what is inside the portfolio remains able to continue to fulfill its purpose or strategy.

Interestingly enough, in the corporate world, when the term portfolio comes up, it tends to refer to a ‘static snapshot’ of a company’s products and services, which we refer to here as solutions. Instead of actions like “re-balancing, and diversifying” being tied to the corporate portfolio, discussions tend to revolve around the questions: what is in my portfolio, and how does it compare to what my competitor has in their portfolio? It is static, and whenever an action is tied to portfolio, it is always about “adding to the portfolio”. At the end of the day, building a corporate portfolio of solutions is treated like a numbers game – if I have more and better stuff to offer than the competition does, I will win more often than not.

Almost everybody has some form of Financial Portfolio management strategy in place, whether they are working with someone from Charles Schwab, leveraging a robo-advisor, or doing it themselves. Yet very few companies have ongoing portfolio management. Why does your neighbor, with $100k in his brokerage account know the name, phone number, and kid’s name of his portfolio manager, when most businesses with a portfolio of solutions capable of generating hundreds of millions of dollars per year can’t even identify who within their organization owns the portfolio’s strategy and its sustainable success? A Financial Portfolio and a Solutions Portfolio aren’t so different from one another. In fact, I will make the case in this blog that:

1) They are very similar;

2) Managing a Solutions Portfolio is more important than managing a Financial Portfolio; and

3) It is easier to do than you think.

So why does the Solution Portfolio get sub-optimal attention?

Spoiler Alert – it’s because nobody is really talking about it.

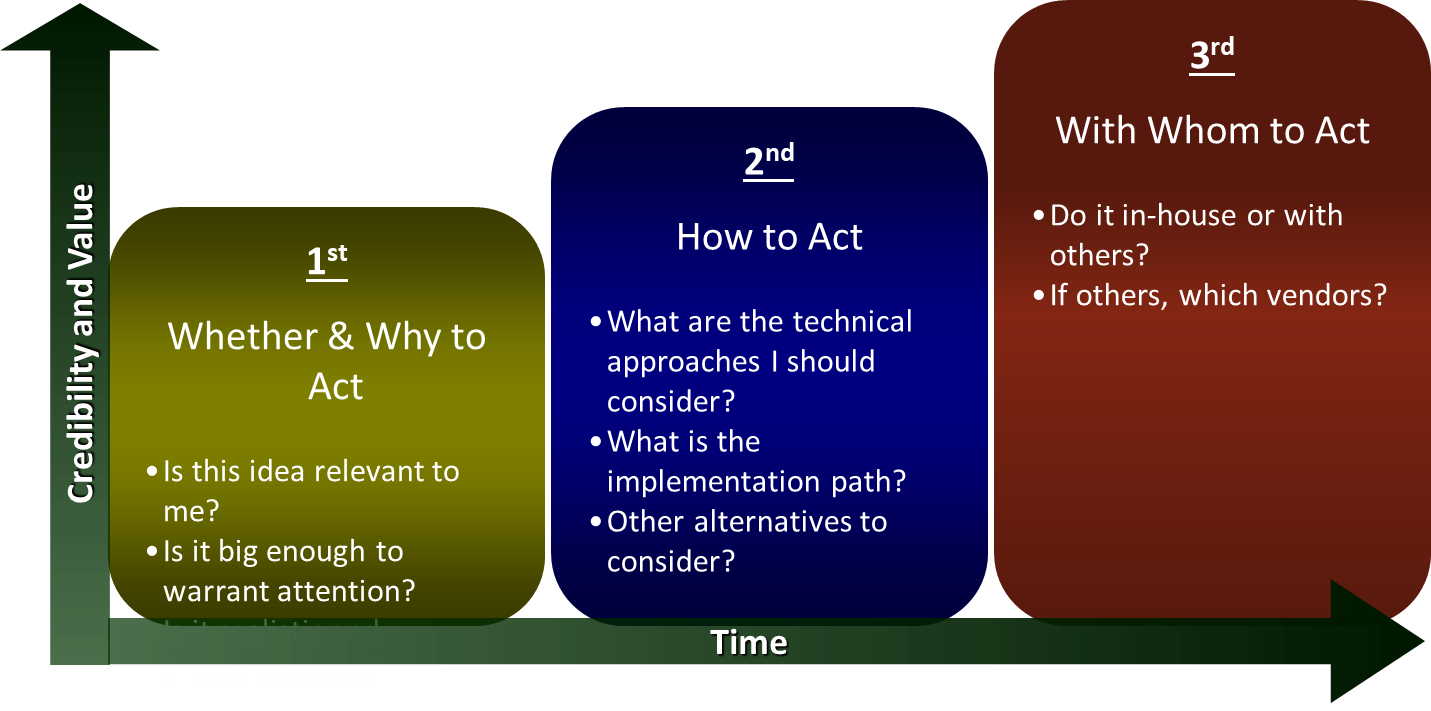

Earlier in my career, I did some personal financial planning, and all the time, people would come to me and ask a seemingly simple question, “how does my portfolio look?” expecting an equally simple answer. Of course, the answer is not simple. In reality, it’s unanswerable without first diving into some of the questions buried beneath it. When someone is asking that question, there are actually wondering:

- Does my portfolio strategy align to my current goals and objectives?

- Do the things in my portfolio align to my portfolio strategy?

- Knowing what there is to know about the market, should I adjust my portfolio strategy to better meet my goals/objectives?

As you might expect at this point, analyzing a corporation’s Solutions Portfolio is based on those exact same questions, and answering them requires us to clearly define and understand the strategy. While you might end up with an effective portfolio without first defining your goals, objectives, and strategies, that luck will eventually run out. You wouldn’t give a 25-year-old starting his or her retirement account and a 75-year-old who is dependent on social security income the same portfolio strategy, but if the market performs well over the right time horizon, it may not matter. That is not an excuse to ignore the strategic elements of the question – strategy always matters and the performance against the strategy is a greater long-term measurement of success. Therefore, when we want to define a Solution Portfolio and the role it plays in the Operating Model, we must begin by looking at the Portfolio Strategy and what it entails.

What is a Portfolio? It’s All About the Strategy!

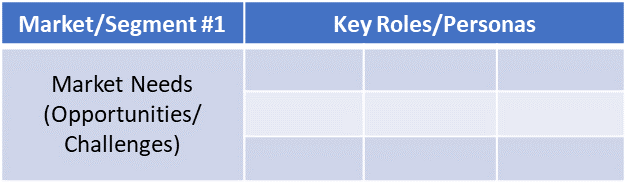

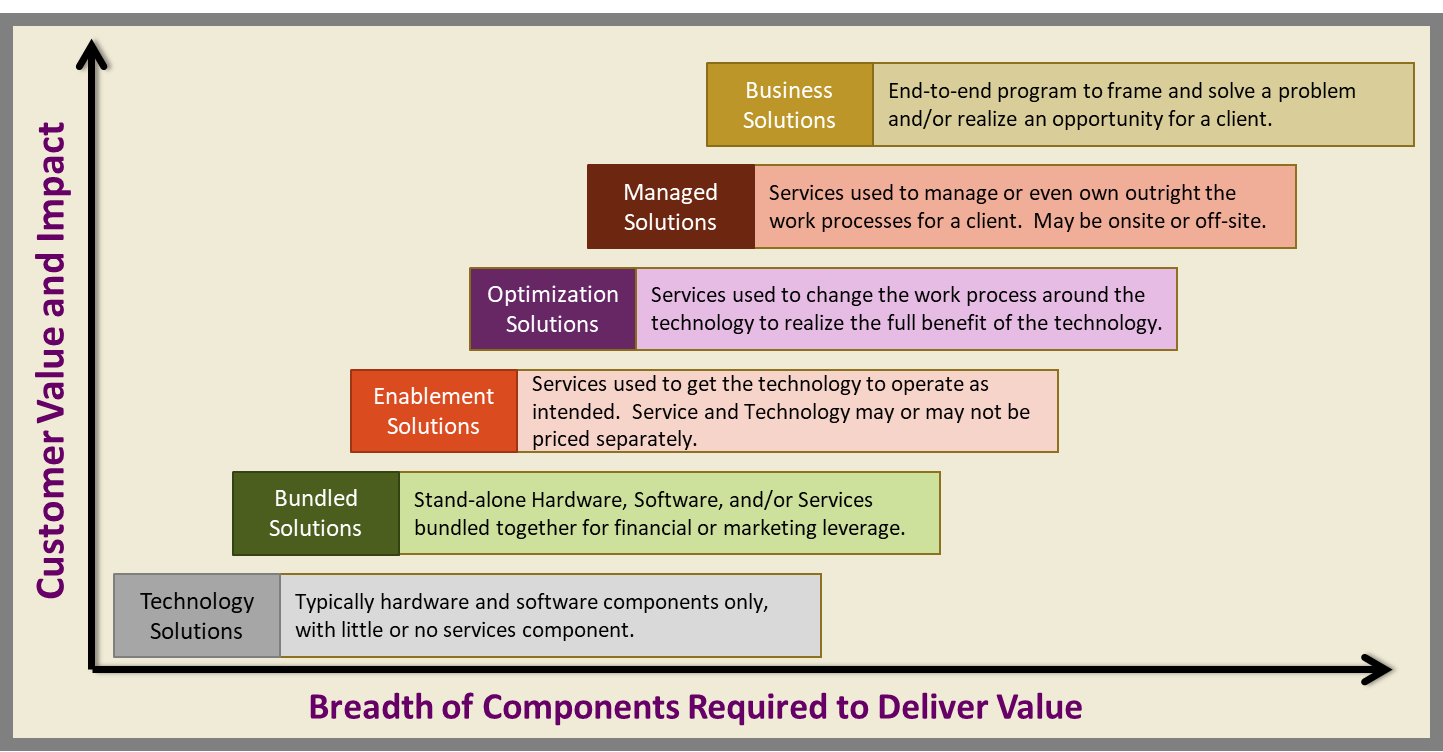

Before we get into breaking down the answer to “how does my Portfolio look?”, we must start at the beginning. At its most basic level, the portfolio is the compilation of all products and services the business has to offer to the market, but as previously mentioned, a portfolio should be the embodiment of the portfolio strategy, which leads us to a more important question – what is a portfolio strategy? The portfolio strategy defines how your organization is going to fulfill the market’s needs. It is primarily informed by:

- The markets you want to play in,

- The buying personas you want to engage, and

- What those markets & buyers need.

Notice anything interesting about that list? All the key inputs are about the market, not about existing products and services. If you are like most organizations, you may be wanting to begin the portfolio process by asking the question “what do we have, and how do we sell more of it?” It’s an understandable mistake. The belief is, that since the portfolio is a collection of the things the business has available to sell, the portfolio strategy should, at the very least, include the current solution set. It is right to believe that the organization is constrained by its existing capabilities and its strategic objectives, but if you are focusing on inward-looking elements as the foundation of your strategy, you have lost the single most important component of the portfolio & its strategy: the fact that it needs to be market-back.

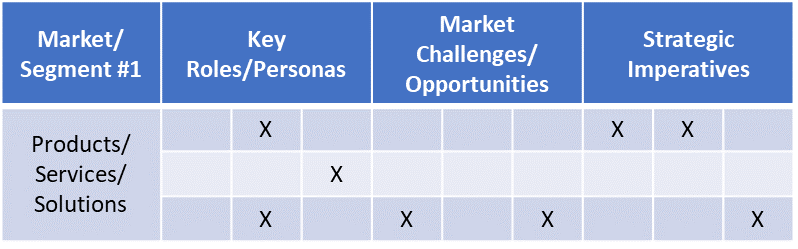

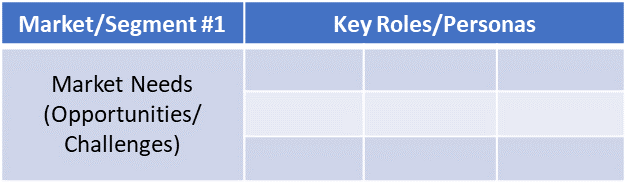

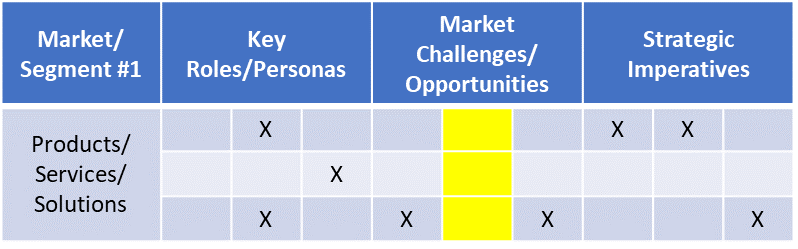

The simplest way to build your portfolio strategy is to begin with a portfolio strategy blueprint, that incorporates all the key inputs, beginning with those that are market-back. Once complete, the portfolio strategy blueprint will be a visual representation of where opportunities exist, and what your organization needs to do, from a portfolio standpoint, to capture them.

Market Back Portfolio Strategy Blueprint

Once you have considered the market-back elements required of an effective portfolio strategy, you can look into the organization and ask yourself, how do my broader strategic imperatives align with or impact this? Up to this point, the portfolio strategy blueprint will look like other companies that serve the same key market segments as you have identified to focus on, it is now, when the organization’s strategic imperatives are incorporated, that the portfolio blueprint, and ultimately the portfolio strategy, becomes unique to you. The concept is similar to the financial portfolio example – the stocks/bonds that are available and how they are performing serve as critical inputs into the strategy, but eventually each strategy needs to be different because everybody has different goals/objectives. Strategic imperatives could come from of a variety of sources (corporate or BU driven) and may have varying degrees of specificity, and at some organizations, there could be dozens of them, the goal will be to pick a few that your portfolio could/should impact.

| For example, strategic imperatives could include: increase intimacy with existing customers; get “above the line of safety” at specific accounts; drive material recurring revenue growth; etc. |

Finally, to know how to get to your destination, you must first understand where you are starting. This is when the current capabilities/offerings are incorporated into the portfolio strategy blueprint.

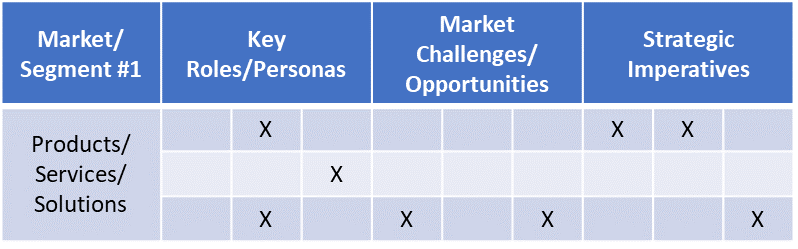

Completed Portfolio Strategy Blueprint

Now, with a clearly defined portfolio strategy blueprint, simply glancing at the visual representation of our portfolio, we can begin answering all of the sub-questions related to“how is does my portfolio look?”:

- Does my portfolio strategy align to my current goals and objectives?

- Do the things in my portfolio align to my portfolio strategy?

- Knowing what there is to know about the market, should I adjust my portfolio strategy to better meet my goals/objectives?

Getting to the complete answer of those questions will require us taking the portfolio strategy blueprint and actually doing something about it – it is at this point where the true value of focusing on the portfolio is revealed.

What Makes the Portfolio So Important?

Now that we have a portfolio strategy blueprint as an artifact, we can use that and our understanding of it to serve the portfolio’s primary purpose – drive the organization’s economic model. The solutions’ portfolio affects the corporate economic model in two ways:

- Informs the investment & product lifecycle strategy for the organization; and

- Enables go-to-market’s success.

The investment and product lifecycle strategy can be derived by looking at the significant “gaps” in the portfolio blueprint.

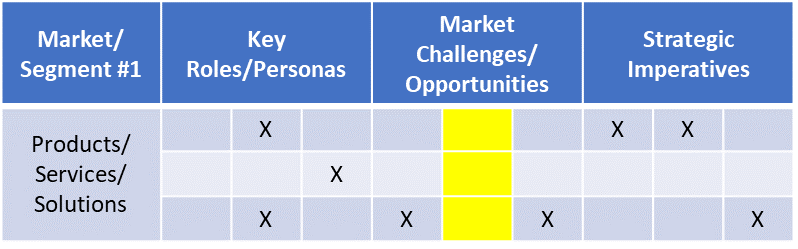

The first gap to analyze, are the column gaps in the market opportunities/challenges section of the blueprint – these will tell you where your portfolio is unable to meet the needs of the market. These gaps are often the ones that require further investment, either to round out an existing solution in the portfolio or to create a net-new product or service. Not all portfolio gaps warrant investment – market analysis needs to be conducted to determine the cost/benefit of creating/updating a solution.

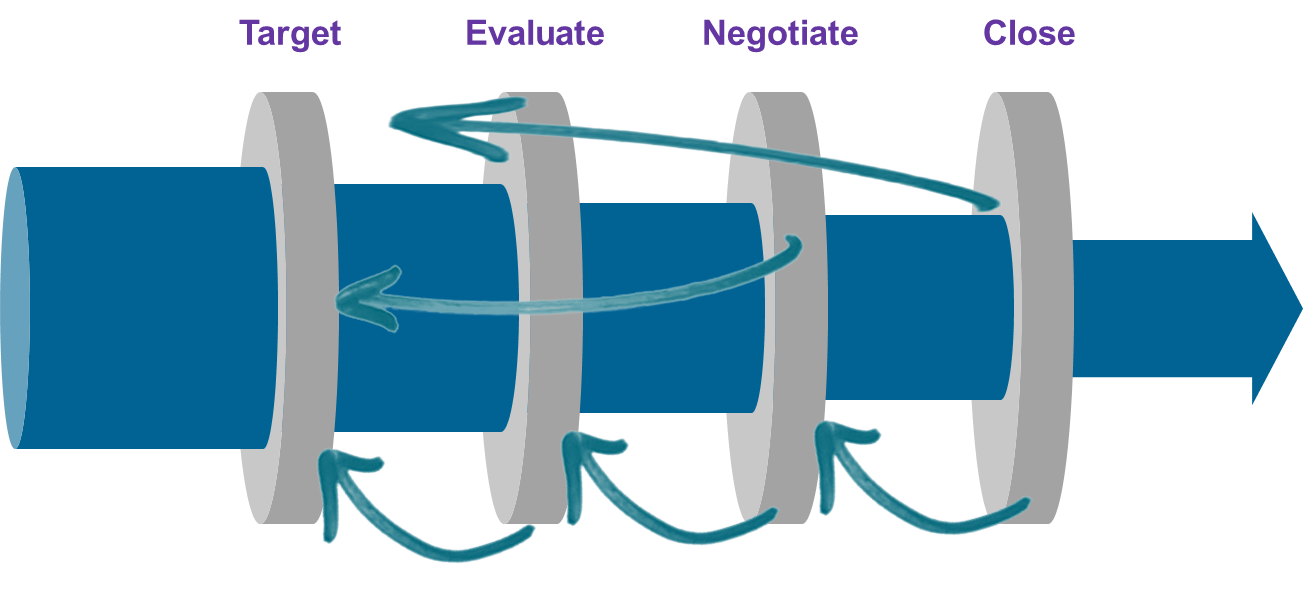

Notice, in the below example, the market challenge highlighted is not met by anything in the current portfolio.

After determining the need for new solutions and new investment, another element that the portfolio blueprint informs is which solutions no longer warrant investment or maintenance. This is either informed by financial performance of the product/service/solution or because of its lack of relevance in the portfolio. Since managing the portfolio is a dynamic process, the market segments the business wants to focus on, the needs of those segments, and the strategic imperatives will change over time, and as they do, elements of the portfolio that historically had relevance and potentially played a significant role, may no longer align with the portfolio strategy, and may need to be phased out so that the appropriate focus and future investment can be applied to those solutions that are best aligned with the needs of the business.

Notice, in the below example, the solution highlighted no longer aligns with any market opportunities or strategic imperatives.

The decisions and implications that result from analyzing the “gaps” in the portfolio blueprint become the portfolio strategy. We now understand 1) which offers; 2) are going to serve which markets & buyers; and, 3) where to round out or parse down the existing portfolio.

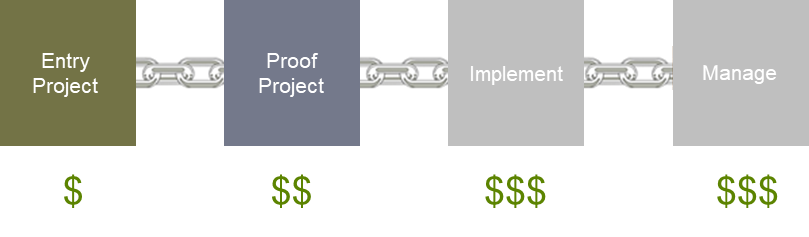

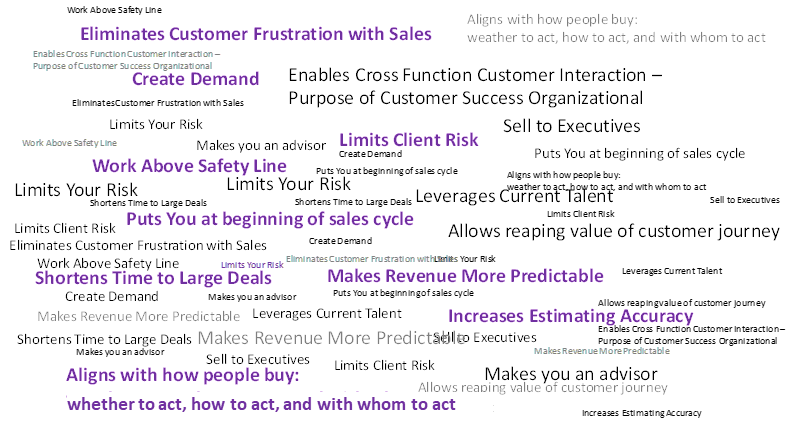

Finally, the go-to-market strategy gets informed by the portfolio blueprint and strategy, this occurs in several ways:

- Clarifies the key market segments and key opportunities to discuss during sales discussions

- Ensures the portfolio investments are made in solutions that will have market applicability

- Informs which offers to “lead with”, or focus on, depending on the segment and buyer

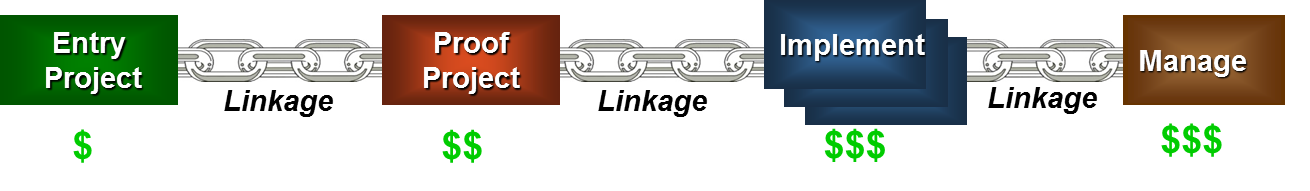

The portfolio is also a critical input into the structuring of Offers and Account Pathways which ultimately have a significant impact into the go-to-market team’s ability to open up new opportunities, up-sell, build intimacy, and much more.

Key Takeaways

- Strategy is everything, without building your portfolio strategy, you might have success, but it will only be short-lived since eventually your differential in the marketplace will run out.

- Because your strategy for each market in which you play is different, each market has its own unique portfolio.

Detailed How-To Guide

- Analyze the market(s) your portfolio addresses.

- What are the high-value sub-segments within the market?

- What are the key topics/opportunities/challenges facing those sub-segments?

- What is the competitive landscape look like?

- Evaluate current portfolio against desired outcomes and overall business strategy.

- Are your products and services meeting the needs of your market?

- What topics/opportunities/challenges does your portfolio address?

- Where are the gaps?

- Are you achieving the desired financial returns in the market?

- Which sub-segments (if any) are underserved?

- Form a cohesive portfolio strategy for a market.

- What topics do you want to own and how?

- Create a plan for “version 1” portfolio.

- Which gaps are strategically important to fill quickly? Which ones are “low hanging fruit”?

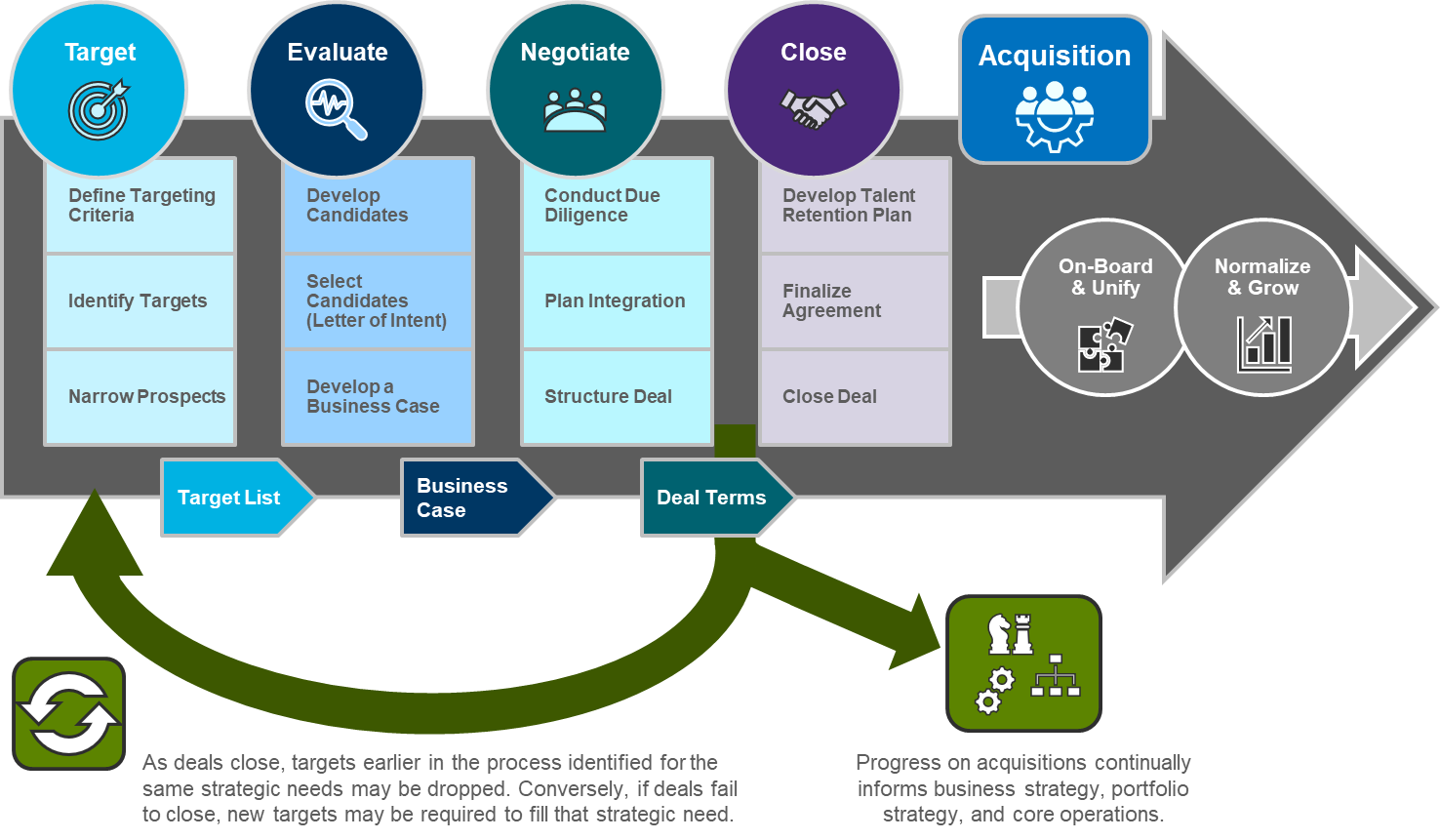

- How will you fill high-priority gaps?

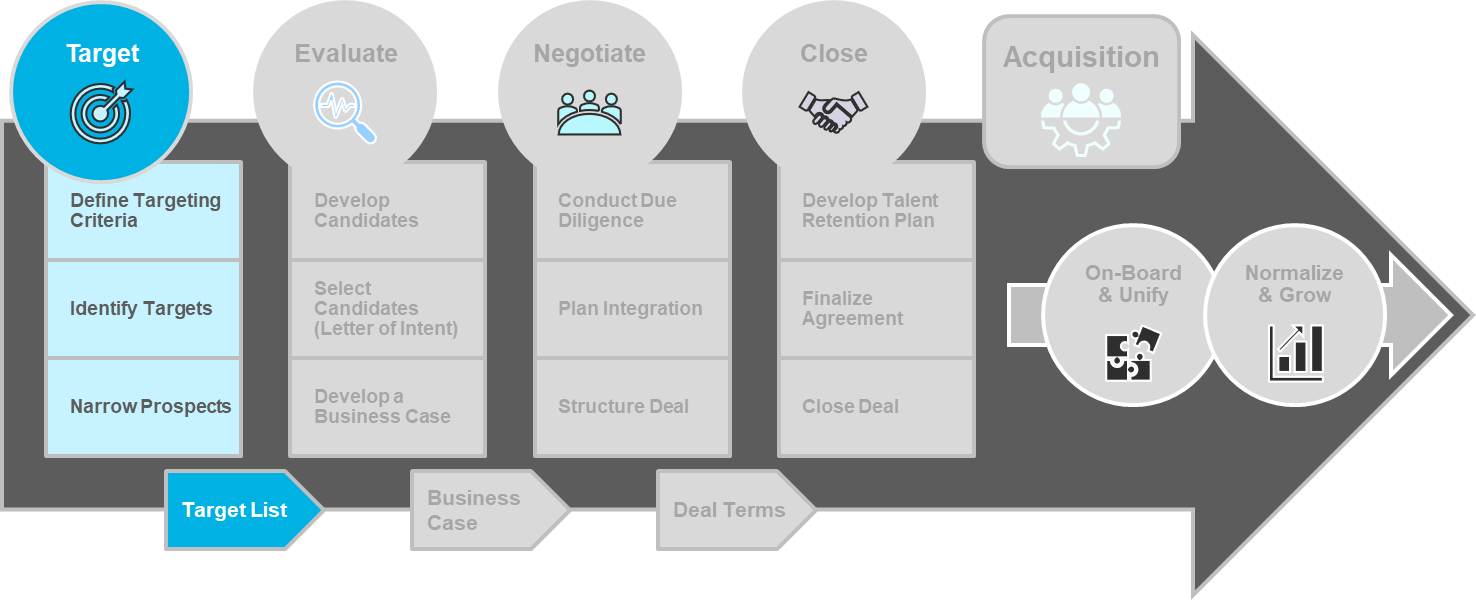

- Acquire new capabilities

- Develop new capabilities

- Reframe current capabilities around a new topic

- Who will own the portfolio strategy and manage the lifecycle of the portfolio?

- Establish portfolio management function.

Written by: Anthony Paluska

More from this Author

About the Author: Anthony Paluska is a Partner at McMann & Ransford with experience helping organizations overcome commoditization by developing stronger, more intimate, relationships with their customers. He has leveraged his management consulting, problem-solving, and change management skills to support 15+ Fortune 1000 organizations, across a multitude of industries.